Why our health records don’t tell our whole stories

I like to keep up with news about health innovation, technology, and startups. I find it interesting, and as a designer working in healthcare I need to stay informed.

In browsing healthcare technology news from various outlets, I’ve noticed that a lot of it is about health data — how it’s siloed (sorry to use that word); how and why it should be aggregated; how it should easily flow between systems; how patients should own and control it.

These are all true and good things. But I’ve noticed that there’s a ‘holy grail’ mentality when it comes to interoperability and aggregation; a sense that if we could only bring all the data together in one place, we’d finally have a complete picture of a person and be able to diagnose and treat them more effectively.

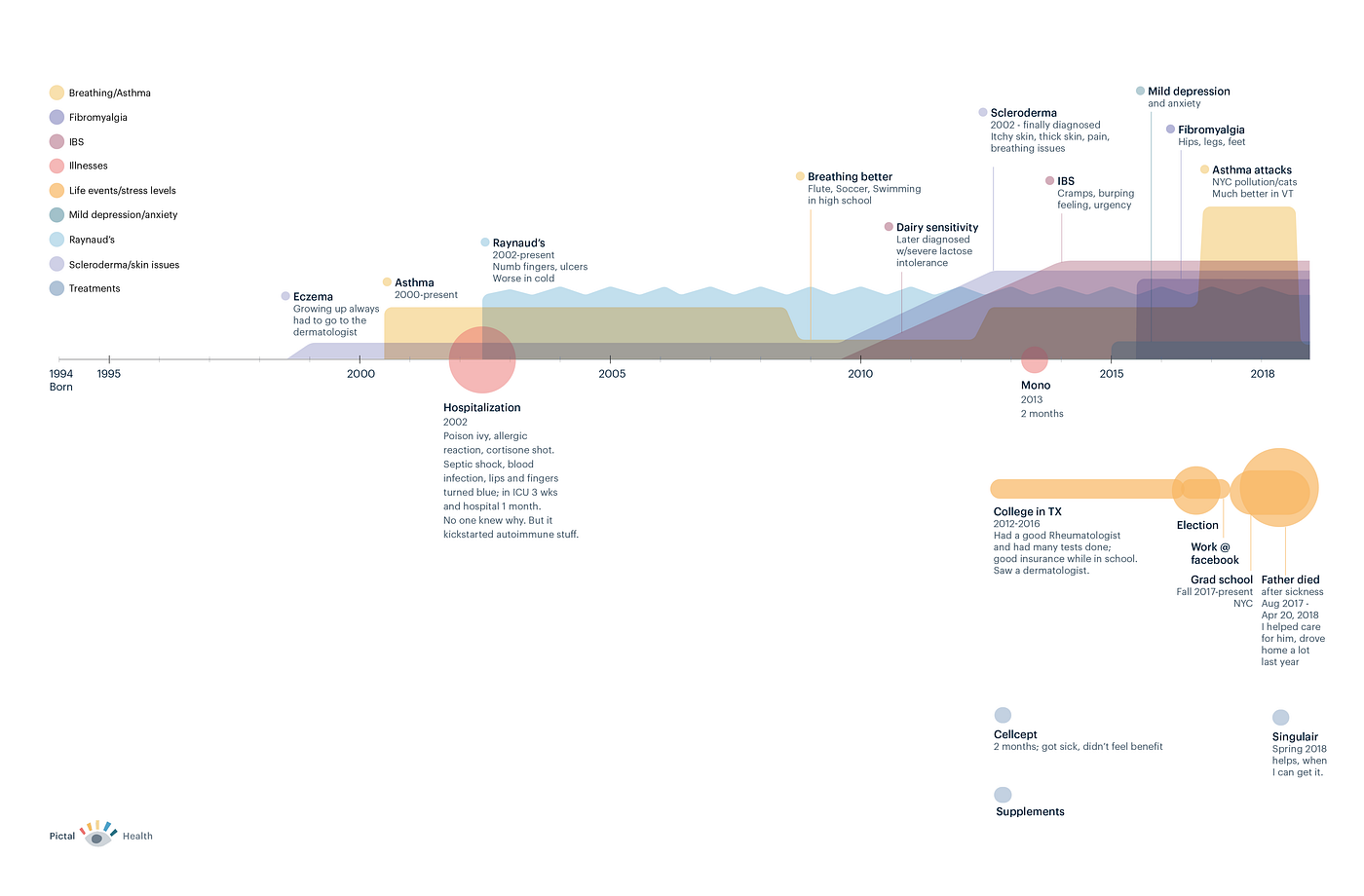

In my recent work helping patients assemble and communicate about their health histories with Pictal Health, I’ve learned about what information they consider important and spent a lot of time working to visually represent that information. Their stories are filled with life events, theories, feelings, and nuance only they can provide. Here is a sample patient timeline:

When I compare these visual, holistic stories to the health records I’ve encountered, I can say with confidence that data aggregation alone cannot produce a person’s whole health story. Here are a few reasons why.

1. Medical records have rampant errors.

An estimated 70 percent of medical records have errors. These may be egregious, like Abby Norman’s record incorrectly stating she has 8 sisters(she has none), or they might be small, like a name misspelling.

My own medical record has a ‘problem’ (diagnosis) that is no longer active, and honestly it’s an embarrassing thing that I’d like to have archived off of my active problem list. Every time I go to the doctor and have an ‘after-visit summary’ printed, it shows this private issue on it. I’ve tried to get it updated a few times, and I haven’t had any luck. Unfortunately, it’s not uncommon for patients like me to have difficulty fixing medical record mistakes.

Sometimes our medical records misrepresent us because of their inherent limitations, rather than outright errors. I recently worked with a woman who accessed her medical records from a large California hospital system. She gave me a complete list of all of her conditions, medications, allergies, etc; her medication list in particular had over 50 items on it, many of which she did not recognize or was sure she never actually took. Our medical records are good at showing when a medication was prescribed, but bad at indicating whether we took the medication or for what duration of time. In order to put together an accurate picture, we had to groom through her data manually and determine which medications she took, and fix the dates associated with them.

So, while our medical records are important repositories of our history, they’re often filled with medications we never took, diagnoses entered by accident, and conditions we no longer have. Bringing all of this information together is helpful and a good first step, but we also need a process of sifting through it to fix the errors, omissions and inconsistencies; patients should be at the center of this process.

2. Medical records have a ton of data; not all of it is relevant to your story.

The sheer amount of information collected about us in our records, especially if we’ve had multi-day hospital stays, becomes overwhelming. Lab tests, doctor’s notes, procedure results; our records become a swirl of medical and scientific facts, billing codes, doctors’ thoughts and opinions about what’s happening with us, and more. This information is vital and life-saving in many cases.

But it can be paralyzing to try to make sense out of the huge amount of data about a given patient, and medical record systems do not make it easy to understand the big picture. Providers are forced to click through many different sections of the chart and read through a lot of old notes to try to get a sense of a person’s story. Multiple healthcare providers have expressed a variation of the following statement to me:

“It is incredibly painful to find a patient’s story in their chart.”

There are surely insights to be gained through natural language processing and machine learning, but these findings will nonetheless always be constrained by the limited nature what’s actually included in our records. Which leads me to my next points.

3. Aggregation is mostly about digital data, but unless we are very young, a lot of our story is still on paper (or in our heads).

I was born in 1978. When I was growing up in the quaint hamlet of Cadillac, MI, my doctors took handwritten notes or typed them up. I do have some photocopies of paper records from a neurologist I saw in my teens and twenties, but at this point, my earlier childhood records are very likely no longer around; according to the Miller Canfield lawfirm, “Under the Michigan Public Health Code, medical records must be retained for a minimum period of seven years following the last date of service provided to a patient.” So if my mom and dad didn’t request print-outs of all my records when I was young, those records are now probably gone.

But a lot of interesting things happened when I was younger. I had allergies throughout childhood, stomach issues as a 10-year old, swollen joints and overuse of antibiotics as a tween, and other precursors to autoimmune and rheumatological conditions. No doctor would be able to find those details in my current digital medical record, but in telling my life story I wouldn’t want these factors to be left out.

4. Large swaths of our human existence are not captured in our medical records.

- Our symptom and bodily experiences are not well-represented in our records. Medical staff ask us how much pain we feel on a 1–10 scale, but this doesn’t capture important details about the quality of our pain, what it looks and feels like, how it travels, and more. The pain scale is a blunt tool, and a one-dimensional view of how we are doing at any given moment; it does not tell much of a story.

- When we look into our deep past, we can often remember times when our symptoms were worse or better; these stand out as symptom milestones of a sort. In October of 1997, I got double vision for the first time and had to have a series of plasmapheresis treatments. I no longer have any records from that time except some spotty doctor’s notes, but I clearly remember what happened, almost to the week. Sitting in the back of a large lecture hall, I recall squinting at my professor and being unable to focus correctly on him unless I closed one eye. In November 1997, I trekked across frosty campus sidewalks at dawn on my way get my plasma exchanged (3 days per week) at the University of Michigan medical center. I also started taking prednisone for the first time, and I was embarrassed to see my face swelling up (a common side effect) even while I was relieved that my symptoms were subsiding. These events aren’t easily available in my current medical record, but they are foundational to my personal journey, and they are easy for me to recall — often with a cinematic level of detail.

- Many parts of ‘life’ that have a direct impact on our wellbeing, such as stress, traumatic events, social support, exercise, and diet are not well-captured in our medical records. Consider how a death in the family, a divorce, being laid off, or moving across the country might impact your health; these are some of the most important events of our lives, but our doctors can’t easily locate them in our records.

- Stress, in particular, is something we talk about all the time; we read self-help books and articles, we meditate, we exercise, we medicate, all in an effort to reduce our stress. But stress, as a concept, is not well-represented in a structured way in our medical records.

- Related to stress, mental health (not just mental illness) is often a gaping hole in our medical records. If I see a private therapist because I need emotional support with some aspect of my life, that fact is not likely to make it into my medical record. But since our mental and physical health are so intertwined, it would be helpful for my doctors to know if I’m going through a rough patch mentally.

Conclusions

Go ahead, put all my health data together into one big pile. It’s an important first step, but it’s still going to be missing about half of my story.

We need to work with patients to groom and refine the data, discard the junk, and add layers of meaning. We need to enable people to tell their whole health stories, not just via the structured data that exists in our health records, but to represent the multiple facets of their mental, physical and social health.

Because the fact is, important clues lie in our stories that could help us get the correct diagnosis and treatment.

I care about this partly because I’m working on a way for patients to tell their health stories visually, with Pictal Health; but it’s also the right thing to do.